Tiny grains, big data: the Global Pollen Project (crossposted from Methods.blog)

The Global Pollen Project is a new, online, freely available tool developed to help people identify and disseminate palynological resources. This article was originally published for Plant Conservation Day, on Method.Blog.

The Global Pollen Project is a new, online, freely available tool developed to help people identify and disseminate palynological resources. Palynology – the study of pollen grains and other spores – is used across many fields of study modern and fossil vegetation dynamics, forensic sciences, pollination, beekeeping, and much more. This platform helps to facilitate cross/multi-disciplinary integration and discussion, outsourcing identifications, expertise and the sharing of knowledge.

Pollen’s Role in Plant Conservation

Successful conservation of rare, threatened, and valuable plants is dependent on an understanding of the threats that they face. Also, conservationists must prioritise species and populations based on their value to humans, which may be cultural, economic, medicinal, etc. The study of fossil pollen (palaeoecology), deposited through time in sediments from lakes and bogs, can help inform the debate over which species to prioritise: which are native, and when did they arrive? How did humans impact species richness? By establishing such biodiversity baselines, policymakers can make more informed value judgements over which habitats and species to conserve, especially where conservation efforts are weighted in favour of native and/or endemic flora.

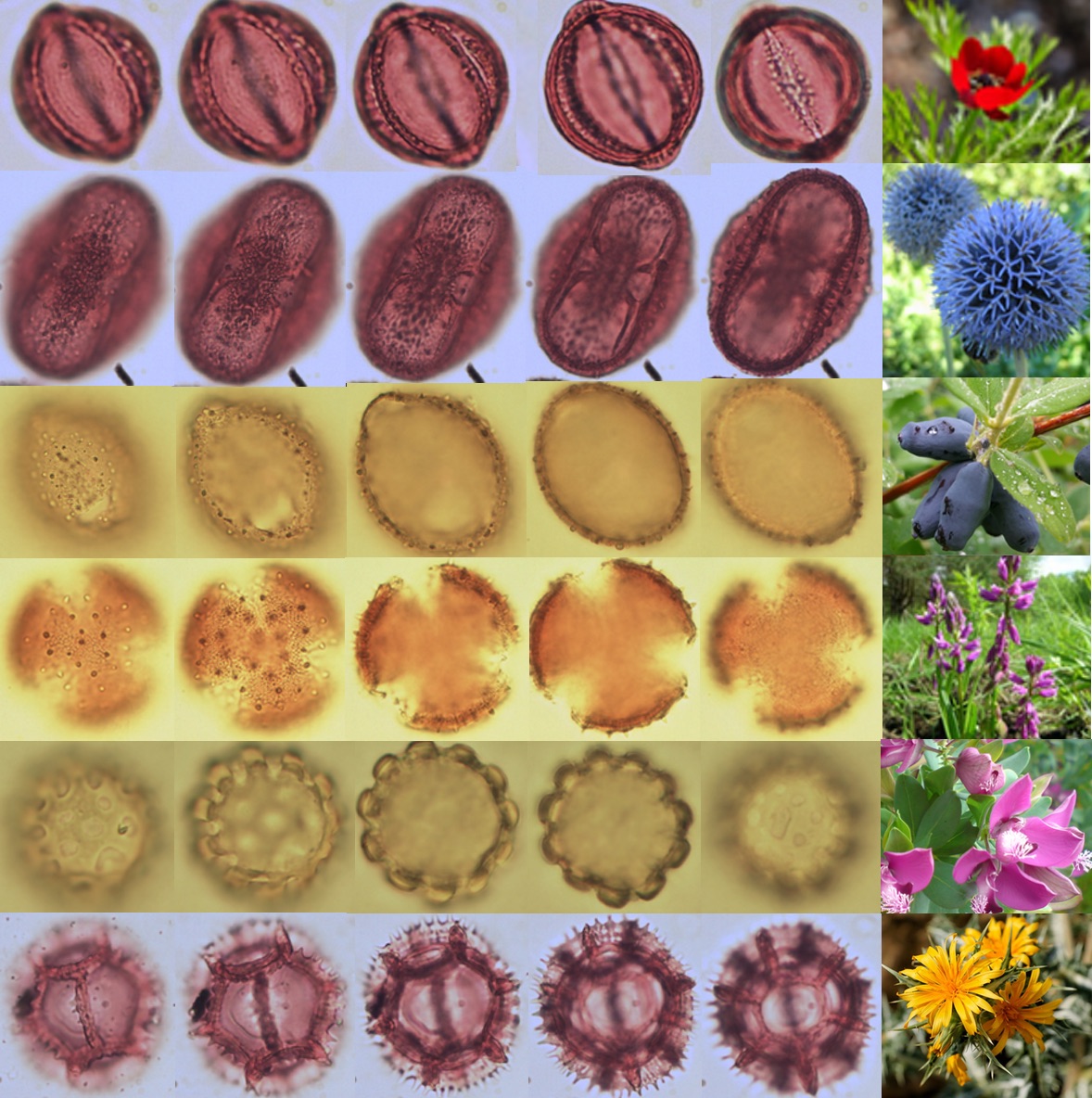

A selection of pollen grains from the Global Pollen Project

Fossil pollen also contributes greatly to our knowledge of spatial-temporal dynamics of plant populations through time. Using this information, it is possible to assess the resilience of species to environmental change: how have changes in past climate and environment influenced the presence of certain species? Where did they persist and where did they die out? Such research can assist efforts to understand how resilient plant populations are to future climate and environmental changes, showing us which areas will be suitable now and in the future.

The Process of Pollen Identification

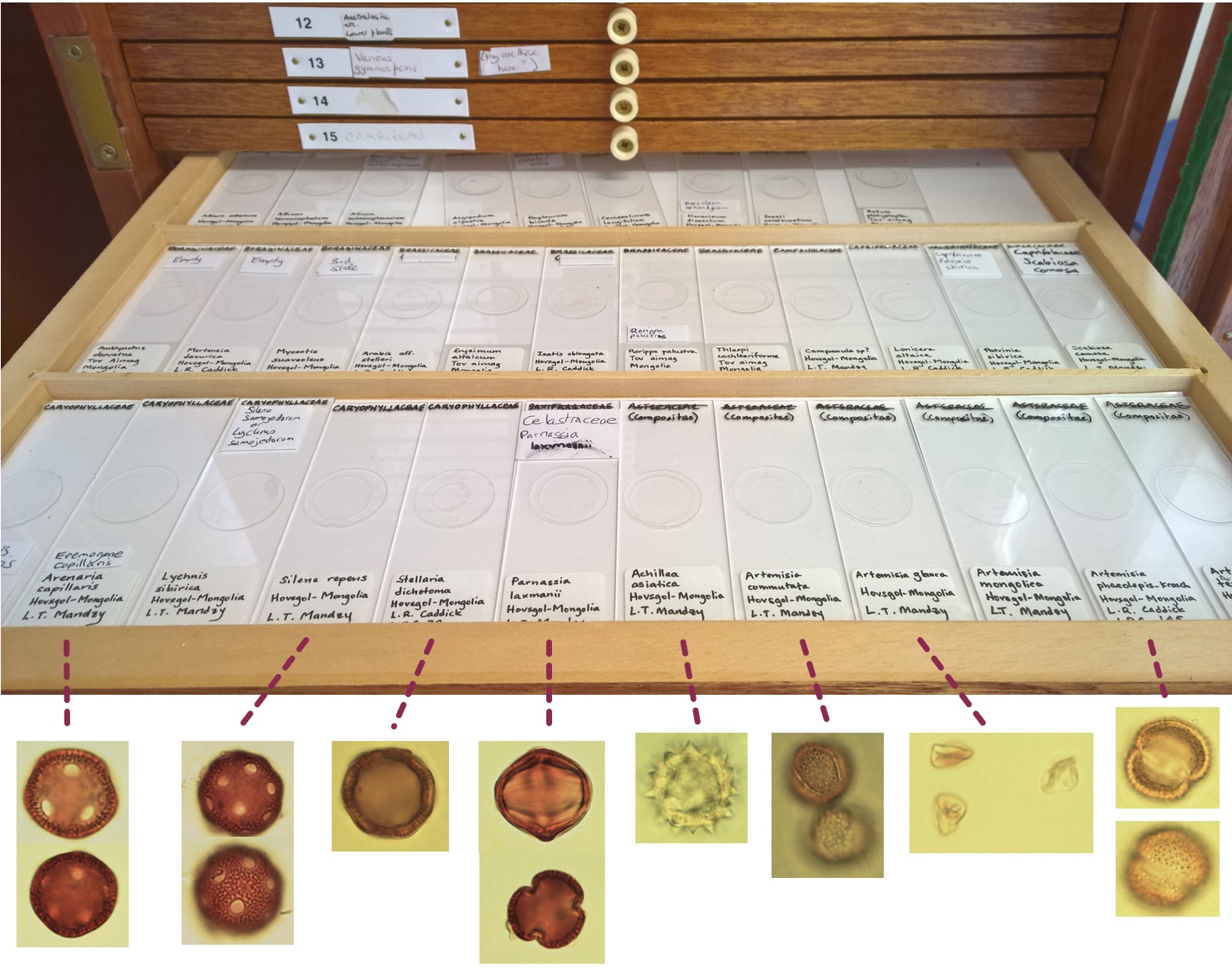

A major limitation when using pollen to inform biodiversity conservation is taxonomic identification. The identification of a pollen grain to a plant species is traditionally carried out via morphological analysis under a light microscope. Each grain is compared morphologically to reference material in the form of reference collections. These collections are often only accessible in the form of glass slides (like in the image above) or in printed books, which are bound to a specific physical location, limiting their access and use.

The pollen identification and counting process is labour intensive. Identification is conducted based on the morphology of pollen traits, such as their size, shape, pores and furrows, surface patterning, and surface sculpture. This process, by its nature, is hard to replicate, with identifications requiring the build-up of significant identification skill, especially for tropical environments with high species richness. The ease of identification also depends on the location and preservation of grains. For example, pollen from dry, tropical environments tends to be more degraded, which makes it harder to give a species identification. So in the tropics, there’s a significant overlap between rare and threatened biodiversity, and difficulty in pollen identification.

The Global Pollen Project: Crowdsourced Identifications and Global Reference Material

To help make pollen identification quicker and easier, we developed the Global Pollen Project (GPP) – an open, peer-reviewed database of global pollen morphology, where content and expertise is crowdsourced from across the world. Our approach to developing this tool was open: open code, open data, open access. It connects to external services, including the Global Biodiversity Information Facility and Neotoma Palaeoecology Database, to provide botanical descriptions and occurrence data for each taxon, alongside pollen images and metadata. There are currently two major avenues through which data is fed into the GPP: digitisation of reference material and the submission of pollen grain images of unknown taxonomic identity.

Digitising Pollen Data

The digitisation of existing reference material is at the heart of the GPP, providing the bulk of the digitised information. Most submitted reference material is modern and sampled from individual plants. This means that it has greater taxonomic confidence than morphological identifications. The digitisation tools are also open to any researcher – from large institutions to individual PhD students – to archive their pollen reference material, and stop it lapsing into ‘dark data’, or becoming degraded. We emphasise the importance of focusable images (or z-stacked images), which provide essential depth-based perspectives on the 3D structure of grains (although we do accept static images too). You can see some examples here, here, and here.

Crowdsourced Identification

A key aim of the GPP is to help improve identification skills through sharing and learning. Users can submit images using a fixed microscope camera, or even a smartphone, providing additional spatial-temporal metadata, which then enter the pool of unidentified material. Other users can then submit morphological identifications to family, genus, or species rank. The GPP weighs up different types of taxonomic identification using in-built algorithms and provides a ‘confirmed’ identification to the material when conditions are met (we currently require at least three identifications with an agreement of 70%). Such ‘confirmed’ grains are then added to the global reference collection with its metadata. In this way, crowdsourcing identifications provides benefits to the submitter and the wider community. To incentivise identifications, each unknown grain has an available score, which an institution or individual can gain through helping to identify the grain in question, providing friendly competition between labs (there’s nothing wrong with a bit of healthy gamification).

Education

The GPP has been incorporated into undergraduate teaching in many institutions since its launch, including the University of Southampton and UCLA. Although offline ‘physical’ reference sets are still useful, this tool can provide access to training in places where large reference collections are not accessible. It also preserves material for the long-term, ensuring that it will be available to the next generation of students.

Bridging the Gap – Palaeoecology to Biodiversity Conservation

Palaeoecology can provide rich insights into environmental history that are highly relevant for plant conservation concerns. With the GPP, we have attempted to bridge some of the divides that limit the direct applicability of pollen research to biodiversity conservation.

Translating Botanical Nomenclature

Pollen research has traditionally used morphological types are the basic taxonomic unit, which do not necessarily translate to botanical species or genera. The GPP was constructed with a dynamic taxonomic backbone. This currently uses the latest version of The Plant List, ensuring that every identity within the system matches a confirmed taxonomic name. The Plant List is the only complete working list of all known plant species detailing all current accepted names and synonyms in floristic taxonomy. Pollen morphotypes are sometimes used in taxonomic nomenclature, particularly in fossil pollen identifications. This is useful and important information, but we think that it’s best preserved as tagged metadata. It’s important to keep this practice separate from attributing pollen grains to their associated plant.

The GPP automatically keeps the botanical identity of every pollen grain up-to-date, by assessing the splitting, clumping, and renaming of taxa through time. The backbone is essential in ensuring that identifications are valid and comparable between pollen grains or slides collected at different times. We also leave the ‘taxonomic trail’ to follow from the original identification, so that the original slides can be traced from digitised slides, even after taxonomic changes. This also lets us directly display our pollen morphology data with modern distributions and data from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

Tiny Grains, Big Data

The GPP aims to provide the first global key of pollen morphology. Although there are still significant taxonomic gaps, we’re working hard to fill them. There are currently 2,877 images of pollen grains in the online reference collection. These cover 167 families, 767 genera and 1,565 species from Britain & Ireland, Europe, North America, Mexico, Mongolia, Madagascar, and the Canary Islands. This expanding collection could be developed to create a more accessible, interactive pollen key, aiding efficiency in pollen analysis, and allowing the pace of data generation to quicken. There is also the potential to ask new questions of the data through the connection of morphology to botany, especially when combined with image-based machine learning.

With the GPP we aimed to bridge the gaps between plant and environmental scientists, ecologists, and palaeoecologists, hoping to stimulate cross-disciplinary research. We hope that better keys will enable more successful differentiation between genera and species, some of which may be of conservation concern while others not, to enable the creation of more accurate biodiversity baselines. Ultimately, this should help policy-makers to make informed judgements about plant conservation.