The Collapse of Norse Greenland: Evidence from Environmental Records

The Norse were travellers by ocean, colonising as far north as Iceland and Greenland, southwards throughout the British Isles, as well as raiding throughout much of Europe. Viking sagas have told us of the voyages of Erik the Red, who led new settlers to the southwest coast of Greenland in 982AD.

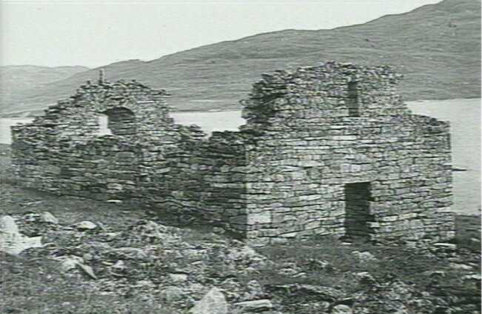

The sagas famously tell of how Erik called the land ‘Greenland’ to make it sound the most promising for new settlers. Archeological evidence suggests that these settlers survived through agriculture, planting corn and herding goats, but the populations ceased to exist from 1425AD. Although the Holocene (around 13000BP to now) is often seen as a period of little climatic change, evidence from environmental archives demonstrates that there were large environmental changes in Greenland that could have been catastrophic for human societies. However, the reason for the collapse of Norse Greenland has long been debated within the natural and social sciences, despite seemingly clear indicators of declining climatic suitability.

A Changing Environment

Most of our understanding of the climatic and environmental conditions in Greenland has been derived as proxy information from ice cores. The ‘Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2’ (GISP2) retrieved a core 3053 metres in length, providing high-resolution data for Greenland. Stable oxygen isotope analysis (δ18O) of the core enabled the derivation of a proxy for temperature, indicating that Erik arrived at the end of a relatively warm period that was more climatically suited for agriculture. During the rest of their period of habitation, temperatures gradually declined. A proxy for ‘storminess’ has also been derived from sea salt (Na+) content in GISP2, with a large spike in ‘storminess’ occurring not long after the last known contact with Iceland in 1425AD. Archeologists have, during the last two decades, greatly increased our understanding of ‘paleodiet’ through the isotopic analysis of human bones. The different plant groups (C3, C4 and CAM plants) and marine food sources contain different isotopic ratios because of their differing photosynthetic pathways, enabling a comparison of broad diets between samples. Interestingly, Dugmore, Keller and McGovern (2007) synthesised the paleoclimate and paleodiet records, noticing that there is a threshold change in diet from non-marine to marine sources coinciding with the most profound cooling event circa 1350AD. The above evidence suggests that the Norse peoples’ method of agricultural food production may have become unviable after a large temperature decrease around 1350AD, with the climate becoming uninhabitable after 1425AD due to increased storminess and ice rafting. As these communities relied on seasonal grazing pastures and corn, the climatic optima of these resources may have been compromised. However, many finer-scale and alternative proxies are becoming available, such as those from chironomids, and should be synthesised for a more complete understanding of any climate impacts.

A Changing Society?

A competing hypothesis to the climate-limitation idea is that of economic-demographic-limitation, put forward by Dugmore, Keller and McGovern (2007). Other peoples in the region, such as the Inuit, continued to persist until the present day. Why did the Norse not adapt to their environment and use alternate technologies? The authors suggest that the Norse food production was reliant on community labour, such as seal hunting, whereas the Inuits sealed year-round as individuals using harpoons and kayaks. Thus, a decrease in the population could reduce resource utilisation of the environment, despite a natural abundance. Trade and the black death have both been suggested as reasons for a population decline. Greenland produced ivory from hunting, but more desirable forms of ivory from exotic climes became available in the Norse trading network. The black death also drastically reduced demand for traded goods, while also creating many opportunities for migrants on the European mainland.

It is clear from the above proxy information that the environment became progressively harsh, and was likely a dominant driver in the depopulation of Norse Greenland. The paleodiet evidence suggests that deteriorating conditions disrupted agricultural production. However, an examination of the social aspects suggests that external economic and demographic pressures may have worked to have accelerate the decline.

Sources / Further Reading

Dugmore, Andrew J, Christian Keller, and Thomas H McGovern. “Norse Greenland Settlement: Reflections on Climate Change, Trade, and the Contrasting Fates of Human Settlements in the North Atlantic Islands.” Arctic Anthropol 44, no. 1 (2007): 12-36

Dansgaard, Willi, S J Johnsen, Niels Reeh, N Gundestrup, H B Clausen, and C U Hammer. “Climatic Changes, Norsemen and Modern Man.”(1975)

Kuijpers, Antoon, Naja Mikkelsen, Sofia Ribeiro, and Marit-Solveig Seidenkrantz. “Impact of Medieval Fjord Hydrography and Climate on the Western and Eastern Settlements in Norse Greenland.” Journal of the North Atlantic 6 (2014): 1-13

Arneborg, Jette, Jan Heinemeier, Niels Lynnerup, Henrik L Nielsen, Niels Rud, and Árny E Sveinbjörnsdóttir. “Change of Diet of the Greenland Vikings Determined From Stable Carbon Isotope Analysis And\^ 1\^ 4C Dating of Their Bones.” Radiocarbon 41, no. 2 (1999): 157-168

D’Andrea, William J, Yongsong Huang, Sherilyn C Fritz, and N John Anderson. “Abrupt Holocene Climate Change As An Important Factor for Human Migration in West Greenland.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, no. 24 (2011): 9765-9769